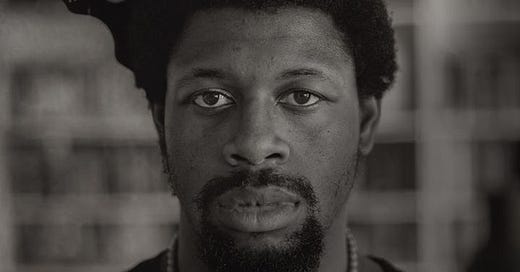

Olúfẹmi O. Táíwò on politics, power, and building a new world

The US philosopher discusses his new book 'Elite Capture', in which he unscrambles power relations old and new to focus on how to move forward.

What links video games, the Emperor's New Clothes, and an armed uprising in Guinea-Bissau? I’m going to insist that you examine the answer in all its detail by reading Olúfẹmi O. Táíwò’s Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics (and Everything Else).

‘Elite capture’, a phrase usually used to describe the magical flight of foreign aid monies into the hands of corrupt officials (whoops!) is broadened here to describe, in only 121 pages, “the way socially advantaged people tend to gain control over benefits meant for everyone” in all areas of life, from grassroots independence movements to Twitter clout.

Táíwò’s new book crystallises the ubiquity of elite capture, opening with a demonstration of how meaning, as well as resources, can be captured.

Leading us through game theory, feminist movements, and junctures in global colonial history, he demonstrates how the original premise of identity politics has been bastardised by surface-level interpretations, and a flimsy version of it then opportunistically seized upon by the right. He goes on to show this as just one example of the ways substantial political movements, ideas, and resources that sustain us are captured, and their potential for transformation neutralised—not via shady conspiracy, but via absorption into existing frameworks of power.

As books on how to understand the world better go, Elite Capture has more depth than most and yet remains accessible (plus, it’s occasionally laugh-out-loud funny). Woven full of relevant themes and tangents it’s the kind of book you won’t just read, but compulsively annotate so you can go back and study it for guidance when you’re feeling out of your depth.

I have an ongoing stream of questions. When so much of leftist thought concerns oppressed vs oppressor, and so much of my phone addiction leads down rabbit holes where this is pursued to the nth degree into a bottleneck of infighting, I’m deeply grateful for the relief—but it’s a lot to remember.

The solution proposed by Táíwò, ‘constructive politics’, feels so far removed from where we are now that it takes a little time to settle into—so I was glad to be able to clarify a handful of things:

Eliz: What is your secret for unpicking these systems in all their complexity? Isn’t your brain fried like the rest of us? (Do I just need to spend less time on Twitter and TikTok?)

Olúfẹmi: My brain is extremely fried! But the secret for taking on these complex systems is simply to not do it yourself!

There's a massive, gargantuan tradition of thinkers and intellectuals that I have been fortunate enough to access and rely on throughout, who have been asking philosophical questions about how our material and political structures connect up: from historians like Walter Rodney and Eric Williams, to theorists like Charles Mills, Oliver Cox and Patricia Hill Collins, to activist thinkers like Grace Lee Boggs and Andaiye.

That's on top of all of a huge community of contemporary fellow scholars asking the same questions and putting these things together in informal conversations and journal articles.

Táíwò draws on a complex web of stories and scholars that show where substantial progressive struggles have, at least in part, succeeded. They range from the revolution of Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau against Portuguese colonisers to the residents of Flint, Michigan whose government poisoned their water, lied about doing so, and forged a safety report instead of fixing it.

The focus of these struggles has been on constructive politics, not those of deference, says Táíwò. It is not symbolic gestures, elites ‘passing the mic’ to the most marginalised, that makes change. Respect is fundamental. But an inflated sense of the centrality of deference, shouldn’t distract progressive movements from building together. It can easily become ‘passing the buck’.

The residents of Flint, Michigan joined forces with scientists to pursue a campaign to clean up their poisoned water system:

“In that moment, what they needed was not for their oppression to be “celebrated”, “centered” or narrated in the newest academic parlance. They didn’t need outsiders to empathize over what it felt like to be poisoned. To be sure, deference politics could give people these things—and these things aren’t unimportant. But they are secondary. What Flint residents really needed, above all, was to get the lead out of their water.” (p106)

Truly radical movements are built of coalition—for example, ones that dare to expose the supposed economic ‘legitimacy’ of enslaving millions of humans, or the supposed economic ‘legitimacy’ of continuing to drill for fossil fuels (at the expense of millions, potentially billions, of humans). But when elites—economic, racial, social, anyone with advantage in a given situation—’capture’ these movements, they’re flattened into thinner symbolic gestures that can be ‘performed’ by anyone, rather than changes in material reality, and are subsequently more easily rejected as flawed.

There is a tiny, funny moment in Giles Terera’s new play The Meaning of Zong demonstrating the distracting desire for individual power vs the necessity for collective action: Black freedman Olaudah Equiano, white campaigner Granville Sharp, and white writer Annie Greenwood are arguing over who should take charge of the priceless shorthand notes Greenwood has written from a pivotal court case.

I wrote them, says Greenwood. I paid for them, argues Sharp. The whole thing was my idea, claims Equiano. Collaboratively, they conclude that the shorthand cannot be interpreted without Greenwood, the legalities understood without Sharp, and the message communicated to the wider world without Equiano. Sharp brusquely announces they will meet at his house in the morning to go over the notes - and exits stage left with the book, to which Equiano asides ‘he thinks it will escape me that he was the one to leave with the book…‘

They are a team working together in the fight to end slavery, in which the white man still grabbed and ran off with the crucial source material. The latter is noted—and it’s a crucial moment of comic relief—but it does not take precedence over the former.

E: There are a number of times when you seem to, in so many words, reject blame and 'cancel culture'—though I don't recall you referring to these specific terms. Was omitting the phrase 'cancel culture' intentional?

O: Yes - I wanted to try to avoid terms like 'cancel culture' and 'woke', that have come to have a kind of pejorative meaning. I think one of the effects of the sort of pro-marketization, anti-community trends of the past few neoliberal decades is that this has amplified a kind of political distortion that is always a problem: the reduction of substantive political discussions to interpersonal questions.

You start the conversation talking about identity politics and you end up with a bunch of insinuations about who's really "authentic" and who's "real". Those are important questions in lots of contexts, but they aren't the same question as the systemic one I was after in the book: which ways of understanding identity have won out on a social level and why? That's a question about social forces, institutional incentives, and the like.

To explain how institutional incentives work, Táíwò embeds the example of ‘the Emperor’s New Clothes’: the emperor’s tailor is hungover, empty-handed, and making up some bullshit for the 9am meeting. The ‘new outfit’ that he hands over is a beautiful garb, he says, invisible only to the incompetent or stupid. Now, of course, the emperor doesn’t want to admit that he can’t see it; once the townsfolk get wind of the claim, neither do they. So the emperor struts around with his cock and balls out, and everyone goes along with it.

For those who aren’t worried that they’re incompetent or stupid, or haven’t yet heard that anyone who can’t see the garments is incompetent or stupid, why might they go along with it? Well, there’s The Implication. No matter what the emperor does, why would you disagree with him? He’s flanked by lackeys holding truncheons, to protect his nudity.

Táíwò argues that almost every social scenario produces this atmospheric pressure. It is simply easier to go along at every juncture; and the fewer resources you have, the more difficult it is to rebel. Rebellion might seem an obvious strategy when you’re young, but once you’re old and tired enough and you have enough evidence that playing along tends to equal reward, and rebelling tends to equal punishment, you just go about your business, not even looking up to acknowledge the emperor’s bits.

Change is daunting, and we’re all products of the system. But we’re not without power.

Young people are currently leading the climate movement, exposing the shriveled nakedness of our governments’ addiction to fossil fuel money. I was relieved to see Elite Capture end on the subject of climate change, and I wondered whether the disruptive nature of the rejuvenated, post-pandemic climate movement fit within Táíwò’s idea of constructive politics:

O: Can't replace direct action! Especially the sort that directly confronts things we're trying to put a stop to: deportations, prisons, pipelines.

My point isn't that we shouldn't oppose things, but that we shouldn't just oppose things - we also have to build the social organizations, cultures, and infrastructure to keep those things going and also everything else we want to achieve.

I think climate change is going to pose a serious challenge to the things we've constructed: physical buildings and infrastructure will get hammered by hurricanes and desertification, political infrastructures will be stretched by distributive conflicts and displacement. So I think we have to respond to our material conditions and not just our principles - that's in and of itself one of the core aspects that the "constructive view" is intended to say something about.

Recent protest movements have been some of the most heavily criticised in the media (mostly, in my experience, by white people) of not ‘passing the mic’. But as I find myself increasingly fighting the hopelessness of eco-anxiety, and the backlash against demands for real change, I’m drawn to how impossible other paradigm-shifting movements must have seemed (can you imagine the whataboutery of 1722?)

I ask if there are any further examples of constructive politics Táíwò would have liked to include, to which he responds with an example: the ‘maroon communities’ built by fugitives of the slave trade, subject to the worst brutality and trauma.

Did the fugitives build a new community based on whose experience was the most difficult? Maybe, they were only human. It’s not about flattening it to be simple, rose-tinted, or other, it’s about deciding what we want to pursue and what we want to leave behind:

O: For centuries, people have escaped the most direct versions of slavery and colonial rule and built maroon communities - in some places they call them palenques, other places "mocambos" or "quilombos", but there are also attempts to literally build something else. These are also things with histories we should think about: what about Quilombo dos Palmares seems like something to carry forward, and what things should we or must we leave behind?

One chapter begins by quoting Bissau-Guinean and Cape Verdean revolutionary Amílcar Cabral on why we need to commit to progress, not simply to deference:

“…foreign exploitation of Africans, has done much harm to Africa. But in the face of the vital need for progress, the following attitudes or behaviors will be no less harmful to Africa; indiscriminate compliments; systematic exaltation of virtues without condemning faults; blind acceptance of the values of the culture, without considering what presently or potentially regressive elements it contains; confusion between what is the expression of an objective and material historical reality and what appears to be the creation of the mind or the product of a peculiar temperament.” - Amílcar Cabral, Return to the Source (p61)

Elite Capture’s final call to action is just as powerful:

“When I think about my trauma, I also think about the great writer James Baldwin’s realization that the things that most tormented him “were the very things that connected me to all the people who were alive, or who had ever been alive.”

[We] have to decide collectively where we’re going, and then we have to do what it takes to get there. Though we start from different levels of privilege or advantage, this journey is not a matter of figuring out who should bow to whom, but simply one of figuring out how best to join forces.” (p121)

Elite Capture is one of the most important books I’ve read for cultivating a dedication to progressive change, and for unscrambling some of the cultural frustration of capitalism and its digital revolution. It’s an essential piece of work for anyone dedicated to addressing the challenges of the decade.

For more media industry news and commentary subscribe to Chompsky: Power and Pop Culture for free OR pay less than £5 ($7) a month to get all my articles and the weekly news/campaigns roundup newsletter 👇👇👇 Thanks!

If you can’t subscribe, you’re still very welcome here. Please share to show your support instead! 👇👇👇 Thank you.