Operation Mindf**k: How To Decipher Adam Curtis’ Ordered Chaos

Curtis’ postmodern style is loved by some and derided by others. In his latest film, it’s a unique playbook for reality.

I just spent over six hours watching all of Adam Curtis’ new film. I won’t say I didn’t understand it, because I mostly did. But it’s probably more accurate to say I felt my way through it, which makes sense for a film called Can’t Get You Out Of My Head: An Emotional History of the Modern World.

It’s a film about how, in the face of a lack of control, humans respond emotionally: either by hunkering down (learned helplessness) or by acting out (following a “strong leader” to authoritarianism) and in either case reinforcing the same old power structures based on stories that turn out not to be true (I… think).

It’s also a sweeping record of over 100 years of global history, bouncing between the rise of disaster capitalism, the fall and aftermath of the Soviet Union, the many revolutions — or not — of China…

This might sound like your average history documentary. But it also makes direct links between these geopolitical timelines and the ongoing US opioid epidemic, the lives of Tupac and Afeni Shakur, and how a Playboy writer invented the idea of The Illuminati as a joke, in a scheme called ‘Operation Mindfuck’. As is the Curtis way, all of these strands are illustrated not only with relevant historical archive footage but also clips of pensioners dancing in a village hall; a 1950s beauty pageant; the interior of an abandoned shopping mall.

Charlie Brooker describes CGYOOMH as “the best” and “perhaps the most accessible thing” Curtis has ever made. His technique of weaving ‘random’ archive footage into dizzying narratives has been described by some as style over substance (although, given that the style is a key part of their being cheesed off, I’m not sure this argument really holds).

For his latest entry, however, Curtis’ chaotic and non-committal style makes perfect sense — it reflects exactly the complexity of the world(s) he examines.

The Unreliable Narrator

Any description of Curtis’ work will contain accurate, polite epithets such as “fragmented”, “chaotic”, and “avant-garde”. The truth is that his work is largely inaccessible. His areas of interest are high-level concepts — power; belief; reality — and he’s known for making connections and inferences between disparate events. He challenges ‘official’ narratives — but in their place refuses to stick to any one story or simple conclusion.

We have been trained to expect a linear narrative, with a satisfying resolution. An entire industry is dedicated to teaching people how to create them. Nevertheless, Curtis clearly has a respectable audience size; he’s been producing lauded work in this style for the best part of three decades. There is no one else making documentary like this in the mainstream: structurally, aesthetically, politically. His natural home would be BBC Four, but his last few films have become appointment viewing on (gasp) BBC Two and iPlayer’s front page.

Given how central politics and power are to his work, it doesn’t fit neatly into our usual understanding of left and right; one of the ways in which Curtis’ approach is particularly suited to this narrative superstructure about ‘how we got here’.

He has a leftist family background but describes himself as having a ‘fondness’ for libertarian ideals, and this shows. He’s fascinated by ideas around power and its abuses, and never shies away from decrying the authoritarian right; but he doesn’t believe in the existing leftist project to challenge it.

This is never clearer than here, in which he tracks the Chinese and Russian revolutions’ violent authoritarianism and eventual capitulation to capitalism at the end of the 20th century. He demonstrates the ways in which emotions such as fear, anger, and suspicion simply replicate old power structures rather than creating the new ones promised.

He’s taking the myriad ways in which both right and left grand narratives have failed and continue to fail, and looking at the similarities between them: resentment and the concentration of power.

Complex Complexes

The latter half of the ‘story’ delves into Chaos Theory and Complexity Theory — via the garage where Google had its first HQ, the dot com bubble, and Dominic Cummings — and I wonder if this is Curtis’ true political north star: that no future will work without acknowledging complexity and ambiguity.

On how he felt about the leaders of China’s cultural revolution, Curtis says:

“…old habits of thought and ghosts from that old hierarchical world were still lodged in their minds. It doesn’t in any way excuse their actions, but it does make you realise that if you do want to change the world for the better, you have to deal with all those feelings. You have to find a way of connecting with them and transforming them. Which will be difficult — but I think it’s something a lot of modern radicals shy away from, and instead retreat into that simplified world of goodies and baddies.”

He’s less concerned with determining who’s right, than with what happened, what happened next, and what happened after that. With the rise of Google, we have access to ‘all the data’ of history. Except for the fact that we don’t. We HAVE to curate narratives. The more data we have, the less we can effectively comprehend it (see: context collapse).

Given the yottabytes of data that make up everything that’s ever happened, how could there ever be a single through-line? The weaving narratives here perfectly reflect the realities of globalism (and its precursor: …the globe?) How can there be one correct way of understanding the world when billions of people are performing billions of actions at billions of different stages of life?

“…over the course of even one lifetime, one person can have the same set of facts but change their minds and beliefs many times to try and make sense of the world and their lived experience.”

And representing our lived experience more closely is apparently what he is going for.

It’s a ‘Dream-World’ After All

Contrary to popular advice, Curtis’ work is ‘tell don’t show’: the majority of the information comes via his voiceover. While I doubt it’d work well as a podcast — its visual novelty and guidance aren’t unimportant — its archive material operates less in a narrative sense than an emotional one. One of my film professors used to say that ‘images are leaky’; they give much more away than simply whatever the image ‘is of’.

His stripped-down use of graphics complements the work but is also a necessity. There’s hardly room amongst the narrative slalom for a production value or a complex title sequence. Curtis is exploding the historical and aesthetic grand narratives of the 20th century.

He arguably nicked it off Third Cinema filmmakers and since then companies like VICE have adopted and applied his lo-fi aesthetic to reams of polished content, so it can feel clichéd. But his work remains one of very few mainstream postmodern projects; one which grasps the ultimate meta-nettle, whispering “by the way, postmodernism is bollocks, the world is still operating on modernist principles. You can feel it, can’t you?”

Postmodern life, in which we have an endless array of experiences to choose from and an exhausted mind/empty wallet with which to avoid experiencing them, can feel like an unbearable moving tapestry impossible to grasp. Telling Charlie Brooker about his exploration of the BBC archive and the way in which uncut news footage feels in complete opposition to what ends up in the ‘inevitable doom’ of the programme, he said:

“I went and discovered another level of reality that’s hidden in the BBC. It is all the unedited tapes from which the news stories were cut. They are extraordinary. They’re like a strange, magical world that is halfway between real life and the snippets of doom that we transmit. There are terrible things on them — but the overwhelming amount is just the record of stuff happening. I’ve got hundreds of thousands of hours of it, and the effect of watching it is incredibly calming. It sends you into that kind of dream state we talked about earlier, where you start wondering what happens to all the billions of billions of moments of experience that are never recorded. Where does that all go to? And I find myself drifting off into wondering about what other people’s experiences must have been like in the fragments I’m watching.”

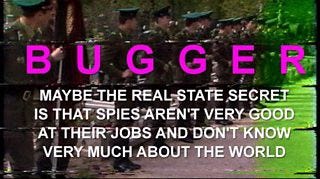

I used to watch a lot of ‘inevitable doom’ documentaries. One of them, before informing me that the world was completely fucked, opens with this intertitle:

This is a good rule for Adam Curtis films. And for life. The only way to enjoy it is with some level of surrender. Let it wash over you, and feel it. We are so used to being told what to do, what to feel, that without this a film can seem incomplete or confusing. But it does give an experience closer to reality.

Fact and Fictions

Speaking to e-flux in 2012 Curtis revealed he borrowed his narrative style from the USA Trilogy, a novel by John Dos Passos. It combines the stories of fictional characters with collages of historical newsreel, and biographies of real historical figures:

“…something that actually tries to evoke a way of sensing similar to wandering along a street and having a mixture of feelings, thoughts from the past, visual things you’re picking up, just stuff that makes no sense, all then turned into stories later on. And I think that’s the great — I’m going to be pretentious here — the great dialectic of our time, which is between individual experience and how those fragments get turned into stories, both by individuals themselves, and then, by the those in power above them. And then there is what gets lost in the process, which is what I think Dos Passos is all about. It’s like when you live through an experience, you have no idea what it means. It’s only later, when you go home, that you reassemble those fragments into a story. And that’s what individuals do, and it’s what societies do. It’s what the great novelists of the nineteenth century, like Tolstoy, wrote about. They wrote about that tension between how an individual tells the story of an event themselves, out of fragments, and how society then does it

This isn’t to say there are no objective facts, that Curtis isn’t using them in his work. In the clip above from 2014, he mentions that people are being prosecuted for decades-old crimes while no one is going to jail for the financial crisis and vast transfers of wealth are still occurring. He’s not doing a deep dive into this (but You’re Wrong About does) nor is he saying that sexual harassers shouldn’t be jailed; he is just using it to talk about the wider concepts of confusion and corruption.

He ends the series with a nod to the potential for the pandemic to change power structures. He posits three potential outcomes, only one of which is hopeful. We can go the way of China: a corrupt society that mass surveils, tracks, and manipulates our behaviour. We can go the way of America: oscillating between, at best, “benign” elites like Biden, and dangerous populists like Trump. Or we can regain our confidence, find our strength, deal with our emotions, and imagine a new way for society to be run.

He finishes on a quote by the late David Graeber:

The ultimate hidden truth of the world is that it is something we make. And could just as easily make differently.

That’s as much simplicity as Curtis fans might ever get.