REVIEW: Sheffield DocFest 2022

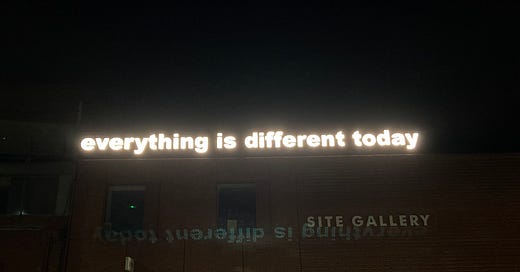

The UK's biggest documentary festival returns, inviting us to reconnect, take 'direct action' and, of course, have a nice time.

It’s my favourite time of the year (bar, maybe, Christmas)—Sheffield DocFest! The largest documentary festival in the UK takes place over six days, an impressive, extensive (and expensive) event far more than just a bill of screenings and parties. DocFest is a primary bit of scaffolding for our international creative infrastructure, a key juncture in the calendar for the development of visual journalism and factual entertainment.

I haven’t been to a DocFest since 2017, and so this year’s tagline—‘ReConnect with Documentary’—was a welcome, if generic, post-COVID brand.

But beyond a simple tagline, DocFest was indeed an example of another post-COVID reunion for a temporarily-stunted industry; it was lovely to see several people I haven’t seen in years, but just that bit more important was the festival’s connection with Ukrainian festival DocuDays, to host what would have been its headline films and projects in development. The DocuDays website explains:

“The 19th Docudays UA was supposed to take place on 25 March – 3 April 2022, but was postponed due to the beginning of the Russian-Ukrainian war. The festival will take place after the victory of Ukraine.”

Sheffield’s international eminence is not lost on attendees. “Sheffield is the main festival for industry. I attend most of the festivals in the UK, and others in the country focus on the public screening programme, which works in their favour—it means they’re not competing,” says Lynn Nwokorie, an executive producer who has worked on three of the films in this year’s festival. “You come to Sheffield if you want to have meetings.”

Sheffield’s focus on the documentary ‘product’ is genuinely exciting and enriching. But like the rest of the industry it doesn’t seem to have got its head around real progressive change. One session, titled “Sustainable Film Production for a Sustainable Future”, was hosted by a streaming company that framed its petition links and awareness-raising via social media views as ‘direct action’. Its panel was made up of three Middle-Class White Guys (really nice guys, but come on) showing clips from documentaries they’d made about nature, who didn’t address any systemic sustainability questions until they came up in the Q&A. The session ran within 48 hours of the following headlines:

Weather tracker: Europe’s heatwave sends temperature records tumbling

Extreme heat causes train derailment outside San Francisco

UN chief warns of 'catastrophe' from global food shortage

I’ll complain some more about systemic issues later. Let’s chat about films! 🫠🫠🫠

The festival’s opener, Moonage Daydream, was a collage film of Bowie’s music and performances; not a traditional documentary, in reflection of Bowie’s less than traditional career.

Fans will love the film. Like Bowie as an artist, deeper meaning can be found or you can simply let it wash over you; either way can be a joy. I admit that I look forward to watching it at my leisure without director Brett Morgen live-mixing it from the back of the room at punishingly loud volume; earplugs were apparently being given out on the doors (I didn’t see any) and several people (who presumably didn’t either) left. I wished the team had refused to indulge him and just let Bowie do his thing - he’s more than capable, as Morgen well knows.

Almost every other film I chose to see happened to be in the ‘Debates’ strand, a solid demonstration of my obsession with socio-political (or ‘issues-based’) documentary. My schedule was a fraction of what was on offer, but I was more than happy with my choices:

The Happy Worker - or How Work Was Sabotaged is a crowd-pleasing, satirically upbeat feature about the similarities between the operations of an average workplace and the US government’s Simple Sabotage Field Manual. David Graeber of ‘Bullshit Jobs’ fame (RIP) and Christina Maslach of UC Berkeley (who coined the term ‘burnout’) are two core contributors, alongside workers who have had breakdowns and/or chronic stress responses to doing admin inside a box for 37.5 hours a week. Tied together by some shocking stats, joyful animations and dream sequences of krumping office workers, it’s a fun trad-doc with something to say.

Immediately afterwards I was treated to a presentation on Navild Acosta and Fannie Sosa’s installation Black Power Naps, which reclaims rest, relaxation and, why not, laziness as a revolutionary, transformative act. People of colour are less likely to get enough sleep, more likely to suffer from sleep disorders, and all resulting problems; the inspiring, soothing presentation from Acosta and Sosa holds the tagline ‘At Black Power Naps, rest is waiting for you! With the full support of your local white institutions’. (This white institution didn’t do enough to prepare us for the fact the installation itself wasn’t in session, only the video presentation.)

Then came a slate of work about gender and, loosely, the so-called culture wars (back in my day, it was just called ‘thinking oppression is bad and Tories disagreeing with you’). Two biopics, Nothing Compares and My Name is Andrea, reframed for me the work of Sinead O’Connor and Andrea Dworkin respectively, given that I’d absolutely swallowed the party line about them both.

I’d deemed Sinead O’Connor irrelevant outside Nothing Compares 2 U and ripping up a photo of the Pope. Visual evidence proved me wrong (this is two weeks post-Pope-rip):

“I like Andrea Dworkin but I’m not down with the anti-sex thing” has been my go-to line since I first heard of her and, again, visual evidence proved me wrong. I couldn’t find the clip of Dworkin on Donahue that director Pratibha Parmar used, which The Hollywood Reporter calls “a telling illustration of the line-blurring confusion that frequently greeted the author’s work”:

[Donahue] continually tells Dworkin what she means, over her calm objections to his reductive interpretation (“Intercourse is bad”). And then there are the comments from the audience. One caller labels Dworkin “very angry and lonely.” Another asks, with a self-satisfied blend of condescension and judgment, “What tragic thing happened in your life that made you feel this way?”

Dworkin is “saying women should stop having sex”, Donahue opines angrily into his microphone. “That’s news to me, by the way” Andrea retorts. I’ve never read Intercourse, the book they’re discussing—something which Donahue and others were, of course, banking on and encouraging.

A complement to these works about shunned women, Céline Pernet’s documentary journey to better understand the modern male perspective, Garçonnières, was a fairly basic talking-head setup, but gave insight. Pernet’s willingness to respect and challenge her interviewees in equal measure resulted in a friendly collaboration in which the interviewees were universally vulnerable. A genuine desire to understand masculinity and men better meant asking questions men tend not to get asked. The result was a testament to Pernet’s skill as an interviewer rather than as an artistically conceptual director.

The corruption of Big Pharma was highlighted by two films: first, The Family Statement, another innovative, spartan short from production company Field of Vision (founded by Laura Poitras of CitizenFour). We’re given fascinating, often banal snippets of a WhatsApp chat between members of the billionaire Sackler Family, owners of Oxycontin manufacturer Purdue Pharma, discussing how and when to make a statement about their company’s misconduct. (Purdue, under the leadership of Richard Sackler, marketed Oxycontin as ‘safe and non-addictive’, then encouraged doctors to over-prescribe in increasingly high doses, single-handedly driving the opioid crisis in the US.)

In the feature-length As Prescribed, a similar story is emerging about benzodiazepines; Valium et al have been ruining people’s lives plenty while US doctors prescribe them like sweets, without informed consent, despite pleas from patients and local lawmakers. Another fairly straightforward actuality doc, following a handful of characters crippled by the effects of benzos, it was informative and moving.

And while we’re on the subject of deadly corporate greed, the stand-out film was The Oil Machine. Rather than another doc that doomscrolls through the ways we’re about to die from global heating, this film by Scottish director Emma Davie reveals the UK’s “hidden infrastructure of oil from the offshore rigs and the buried pipelines to its flow through the stock markets of London.”

It was the first time I’ve ever been interested in the minutiae of pension plans.

Producer Sonja Henrici calls DocFest “a crucial event for the film’s journey” for the way it will introduce the film to both audiences and industry. “As soon as we launched we got interest from other festivals worldwide, sales agents… Sheffield gives a certain stamp of approval. It’s a big piece of the puzzle, with a particular type of clout”.

I asked about the ‘impact campaign’ that issues-based films are required to have these days: “We didn’t want to create a new campaign - there are so many climate campaigns out there and we’re talking to so many different communities in the film [e.g. oil rig workers, fossil fuel insurers, climate activists]. We wanted to pull those communities into screenings, have them host screenings and bring them together, and work with people in the film to see what their recommendations are”.

Partly funded by the BBC, The Oil Machine will be screened by the broadcaster sometime around the end of the year.

Returning to the power dynamics of the event, I want to be fair to the organisers, who genuinely appear to be dedicated to interrogating the industry’s imbalances. I spoke to Rebecca Day, a panellist for the ‘Beyond Centres of Power’ session, a former documentary producer who now runs Film in Mind, an initiative to provide therapeutic services for creatives. Day expressed frustration at the lack of reciprocation from power-holders:

It's heartening to see how many festivals are beginning to include panels on mental health, ethics, power etc into their programming. [Sheffield DocFest] is a key time when the industry all comes together as a whole to collaborate and discuss things. By offering these sessions, DocFest is engaging in the conversation, which is the start of the change that is needed but it was frustrating to see that people in the position to actually act on the needed changes were not in the room… I wonder how we can encourage them to show up to these conversations?

Me too.

Finally, on the accessibility question, I’ve previously criticised DocFest for steep costs. In 2016, I pitched the overall individual spend for an attendee at around £750; this year, producer Geoff Arborne of Inside Out Films told me, it was over £1,000.

“The only reason many filmmakers are able to come is the national delegation process,” he told me. Small groups of filmmakers, ‘delegations’, from certain countries will be funded by their BFI equivalent— this year saw delegations from Chile, Ukraine, Sudan, among others (plus…Cornwall). “There are very few spaces, of course, and so you have to be lucky, or know someone, to get a spot”.

No shade to Past Me, but in 2016 I was an angry young person who had just shelled out several hundred crucial pounds to attend, on top of the discount provided to my film network. I didn’t know about the delegation process (I learned about it this year, from Geoff) and having volunteered twice before, I didn’t consider it a great option, given the restrictions to what you could experience outside your set shifts.

But Kat Padmore, a volunteer at this year’s festival, told me their experience exceeded expectations:

…we're highly encouraged to see as many films as we like and can get into screenings fairly easily. The team really encourage us to enjoy outside of volunteering, and some of my team have seen over half the schedule so far! The team have been communicative, appreciative and a genuine joy to work with.

The event is meant for industry professionals; alongside volunteers and delegates, it’s assumed that the majority of costs will be absorbed by employers such as BBC, Channel 4, Netflix.

But in my conversation with EP Lynn Nwokorie, I was reminded of the heavy ratio of freelancers in this industry. “Trying to navigate being in all those places you need to be can feel like an obstacle,” Lynn says. “I do feel that institutions like Sheffield are trying to make it as accessible as possible; they have different kinds of passes, for example, but there are people who can’t afford to be here and it has nothing to do with talent. My feeling is there is acknowledgement of it throughout the industry, but the wheels are moving a bit too slowly in addressing it.”

As an angry person now approaching middle-age, I can see the nuances of the situation far better. I’m unwilling to put the blame at any one person’s door, but I wouldn’t mind much more realistic tiered ticketing to provide for young indies who want the commissioning opportunities the industry say they’re eager to give, and a serious, radical approach to discussions on urgent issues such as sustainability.

If the creative industry wants to survive and really move beyond existing centres of power, direct action needs to be taken—not hearted, thumbs-upped, or discussed at a roundtable of familiar faces.

Thank you for subscribing! Paying £5 ($7) a month helps to support my work. Please feel free to share this post 👇👇👇

What a great review! Excited to see some of the titles you've cited here