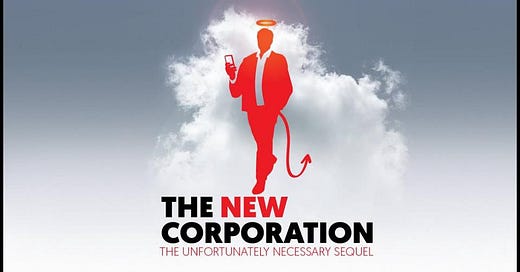

‘This Is What the 2020s Will Be About’: The New Corporation | REVIEW

An ‘unfortunately necessary’ update to 2003’s groundbreaking doc is convincing, provocative, and surprisingly uplifting.

I can’t recommend 2003's The Corporation enough. A polemic about our fabulously irredeemable corporate overlords, it’s full to the brim with case-studies from The Walt Disney Company to industrial flooring manufacturers. It has long been one of my favourite films; my only gripe being its combination of a 2 hour and 45-minute runtime with the most beautifully soporific, velvety narration in cinema history. It was not easy for my teenage brain to digest three hours of information about exactly how and why my future was doomed, accompanied by an eerily erotic lullaby.

But if you can stay awake and maintain your attention span (the trick is to pretend it’s three hour-long episodes of a series binge!) you’ll not only find that the film’s sweeping look at the mechanics of corporate fuckery is more relevant than ever, but that something important is missing. There’s barely a whisper of Amazon, Google, Facebook, YouTube…

The interim is less than 20 years. When The Corporation was released, on the cusp of an explosive moment in the digital revolution, two of those four companies did not yet exist. ’04, ’05, and ’06 saw the launches of Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter respectively and at the end of the decade, other huge corporations would lose none of their influence by causing the worst global financial meltdown since 1929.

And then, of course, came the 2010s. Cue the “unfortunately necessary sequel.”

The New Corporation, by returning director Jennifer Abbott and writer Joel Bakan (Mark Achbar co-directed in ‘03), is a response to two further decades of turbulence and deregulation that they claim have turned us from a society beset by corporate misdeeds into “a society now fully remade in the corporation’s image”.

There’s no doubt that, on this charge, the sequel is convincing, but due to 24-hour rolling news, social media, and the prevalence of doom-docs in streaming culture (including those about how terrible 24-hour rolling news and social media are) this idea is hardly groundbreaking. We get it, they’re evil. We saw The Corporation.

Where the film really succeeds and builds upon its predecessor is in asking its audience to do more, and giving concrete examples of change already underway. Often when documentaries end on a call to action it’s flaccid: ‘visit the film’s website’ or ‘the solution to catastrophic overfishing is to buy your fish in a different supermarket’. This film devotes the entire final third to celebrating changemakers, making clear its belief in the power of progressive mass movements and of democracy, and that corporate rule cannot continue.

Stylistically, there are numerous direct nods to its predecessor: interviewees in the black void — some returning, most new — address us directly. The opener, a mesmerising flicker reel of corporate logos, is given a full-colour and roster update. (This fragmented, hyperactive ‘scroll’ was a prescient visual technique. Watching this sequence in ’03 I remember feeling a little disturbed and nauseous. Now, it simply mimics the feeling of a few hours of doomscrolling.)

The producers, perhaps in response to my years-long vitriolic email campaign, have significantly lessened the sequel’s runtime and replaced our seductive narrator (Mikela J. Mikael and Charles Officer: you each did a great job.) Airtime given to corporate representatives also remains, setting the film apart from many of its contemporaries. Campaigning/advocacy documentaries are frequently charged with being one-sided; while there are elements here to critique (e.g. setting the record for variations on the phrase: “doing good just isn’t compatible with corporate capitalism”) silencing adversaries isn’t one of them.

That said, the filmmakers aren’t pulling punches. As a well-meaning Dr. Shannon May smiles down the lens, resting on her final words about the impact her for-profit schools are having in the world’s poorest countries, another interviewee’s voice cuts in: “it’s colonialism, pure and simple”.

May’s partner describes their approach to education as reminiscent of McDonalds' and Starbucks’ model: ‘systematise and standardise’. While it may appear noble to say corporations should invest in provision of education for the poorest:

“what it is also saying, is that the kinds of change that we ought to pursue are the kinds of change that kick something back to the winners.”

The narrative blueprint remains also, with another update. The Corporation begins by delineating the history of the corporate entity’s construction in law, highlighting three key features which Bakan identifies as its central illnesses: limited liability for individual investors and the framing of the corporation itself to have ‘legal personhood’, and the core driving aim and legal requirement that corporations deliver returns to their shareholders:

“The corporation is deemed by law to be a person that has the same rights as human beings — sometimes even more. So we posed the question, if the corporation is legally a person, what kind of person is it?”

Where before behaviours of the ‘corporate person’ illuminated in each chapter were ticked off from psychologist Robert Hare’s checklist of psychopathic traits (since appearing as an ’03 interviewee, Hare has vocalised mixed feelings about this premise), the updated motif inquires:

“If the new corporation had a playbook, what might it look like? What would its key plays be?”

In a gloriously satisfying turn of events, Hare’s checklist has seen a new criterion added in recent years: “use of seduction, charm, glibness, or ingratiation to achieve one’s ends.” As the film launches into its meticulous takedown of “laughable” corporate social responsibility rhetoric, the chef’s kiss resonates.

#2 in the ‘corporate playbook’ is ‘Turn People Against Your Adversaries’: infiltrate and defund governments > criticise governments for lacking the funding to provide for its people > swoop in to save everyone, in the meantime accruing more wealth and power > allowing you to infiltrate and defund government.

“What you get is this profound anti-government programme, to create deficits through the combination of tax cuts and military spending so as to make it impossible to use government in a positive and constructive way to deal with our social problems.” — Marshall Ganz, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University

Watching clips of politicians taking CEOs to task, outlining the unbelievably corrupt mechanics of corporate politics, it seems amazing that this is allowed to continue. But of course, as one interviewee reminds us: it’s “pretty much accepted that corporations are in charge”.

And still, in times of great need, investment money has mysteriously dried up; corporations have simply no money to bail themselves out, or pay taxes, or pay workers: what does it tell us when corporations are routinely fined billions for their crimes and are still able to stash trillions every year in untaxed profits?

This isn’t just a matter of opinion, ‘who do you think is better at governing, public or private bodies’. This is a matter of life and death, and involves both a failure of government and of corporate DNA, says Robert Weissman of Public Citizen:

“Routinely, when government regulation fails, companies in the pursuit of profit endanger people. And that’s not a hypothetical, I mean these people get poisoned, they get diseases, they get sick. Corners will be cut, people will be injured, and people will be killed. We see it over and over again.”

It’s not for lack of trying, as seen in a clip used of Katie Porter taking JP Morgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon to town:

She may have won the battle, but while it’s inspiring to see this powerful work toward accountability, progressives are losing the war. So we follow the successful journeys of some up-and-coming, grassroots political candidates including Kshama Sawant, a former Occupy organiser, campaigning for progressive change at the local level.

There’s no explicit suggestion that audience members should be running for office, but that work is being done and to support it where we can. To paraphrase a now-disgraced activist I used to like a lot: it’s no use asking ‘yeah, but, does one vote/protest/petition/riot/explosion of a dam work though?’ We need to do it all. [NB: I do not advocate blowing up dams. Or anything, for that matter. But, like, arguably some do need to be dismantled. Just…read Jenny Odell.]

As a piece of agitprop, the film could be clearer about how to fight a battle being waged on an unimaginable number of fronts; it’s overwhelming. But ultimately, not that hard to solve: pick a specific community and/or area of ‘work’. You can’t personally ‘solve climate change’ (unless you can in which case what are you doing here, FOR GOD’S SAKE) but you can find the people already doing that work and help them. Micah White says mass movements allow us to “dream again” where the possibilities for change have seemed so limited. We’ve been told for 40 years that “there is no alternative” and it wasn’t true, but it sure did work.

Documentaries aren’t going to do the work for you. Even if they wanted to, the complexity of this can’t be fully addressed in a feature-length runtime. For example: one of the articles displayed in The New Corporation is ‘Just 100 companies responsible for 71% of global emissions’. Is this true? Well, yes, but it’s more complicated than the headline makes it seem. Full Fact can help you unpick what that actually means.

At the film’s midpoint, writer Paul Mason clarifies the central question that underpins all others: “What do you stand for? Are you actually going to challenge the power of corporations? This is what the 2020s will be about”.

The New Corporation is available to stream in Canada, and premieres in Europe at London’s Human Rights Watch Film Festival from 18–26 March.

You can also join the filmmakers for a live ScreenTalk via zoom at 5pm on Sun 21 March.

For other festivals check out their events calendar. To organise a screening yourself, contact the filmmakers.